Hermann Hesse:

Either a poet or nothing!

Speaker:

Even today the name of Hermann Hesse is linked with the mid-1960s student movement in the U.S.. A rock band which typically took the name “Steppenwolf” sang the title song of the film hit “Easy Rider”, entitled “Born to be wild”.

At that point in time, Hermann Hesse had almost been forgotten in Germany and was as good as unknown in the U.S.. Then, beginning in the middle of the 1970s, Hesse suddenly started to be read again, also in Germany.

This degree of fame, however, led to a misinterpretation of his work!

The Anglo-American best-seller author Colin Wilson, in his 1956 book "The Outsider," analysed the typology of the outsider, with reference to works of well-known people. He dedicated an entire chapter to Hesse, and thereby awakened the curiosity of his young readers.

At that time, a fringe group of the 1960s Beat Generation appeared on the scene, the "Beatniks." Increasingly, this generation mixed in with the teenage subculture, which was shaped by Rock'n Roll, then emerging. In addition, statements by Harvard Professor Timothy Leary contributed to wider circulation of Hesse's books "Siddartha" und "Steppenwolf."

With his highly questionable glorification of drug experimentation, Leary found eager listeners in 1963, and, while still a professor, "he gathered Hesse apostles around his person, like a guru."

That was the period of the Vietnam war, which took the lives of many thousands of young recruits, before the U.S. withdrew in 1969. The American people considered this form of foreign policy with growing criticism. For the youth, especially, the Vietnam war became a hot issue, which was tied to basic questions concerning the meaning of life.

Referring to the wrong interpretation of his novel "Steppenwolf" Hesse said in 1941:

Speaker-Hesse:

"I cannot and do not want to prescribe for my readers how they are to understand my stories. Let each make of them what is in accordance with him and what is useful! But it would make me happy if many of them were to notice that although the story of Steppenwolf presents a sickness and a crisis, it does not present a process leading to death, or to the end; rather, it leads to the opposite: to healing and recovery."

The drifting leaf

(Translation by Walter A. Aue)

Headmost in wind's shoving

waves a wilted leaf.

Roaming, youth, and loving

stops: their time is brief.

Trackless leaves ascend, descend

wherever winds will stray,

only to stop in the woods, in decay.

Where will my journey end?

In the Mists

(Translation by Walter A. Aue)

Wondrous to wander through mists!

Parted are bush and stone:

None to the other exists,

each stands alone.

Many my friends came calling

then, when I lived in the light;

now that the fogs are falling,

none is in sight.

Truly, only the sages

fathom the darkness to fall,

which, as silent as cages,

separates all.

Strange to walk in the mists!

Life has to solitude grown.

None for the other exists:

Each is alone.

Spring Night

In the chestnut tree the wind

sleepily stretches its plumage.

Dusk and moonlight

drift down onto the steep roofs.

Unobserved, moonlit trees

sleep in the gardens.

The breath of beautiful dreams

rustles deeply through the round treetops.

Hesitantly I put down my violin,

warm from being played,

and gaze into the blue yonder,

dream, yearn and remain silent.

Speaker:

Hermann Hesse was a seeker his life long. Not only his great poetical work, which earned him the Nobel Prize in 1946, but his biography bears witness to this.

In the Presentation Speech delivered when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1946, it was said:

"With Hesse, more than with most writers, one has to know his personal background to understand the rather surprising components that make up his personality. He comes from a strictly pietist Swabian family. His father was a well-known church historian, his mother the daughter of a missionary. She was of French descent and was educated in India. It was taken for granted that Hermann would become a minister, and he was sent to the seminary at the cloister of Maulbronn. He ran away, became an apprentice to a watchmaker, and later worked in bookshops in Tübingen and Basle.

The youthful rebellion against the inherited piety that nonetheless always remained in the depth of his being, was repeated in a painful inner crisis, when in 1914, as a mature man and an acknowledged master of regional literature, he went new ways which were far removed from his previous idyllic paths. There are, briefly, two factors that caused this profound change in Hesse's writings. (...)

The first was, of course, the World War. When at its beginning he wanted to speak some words of peace and contemplation to his agitated colleagues and in his pamphlet used Beethoven's motto, «O Freunde, nicht diese Töne», -- "Oh friends, not these notes!" he aroused a storm of protest. He was savagely attacked by the German press and was apparently deeply shocked by this experience."

In his autobiographical notes, published in 1925 under the title, "Either a poet, or nothing," he wrote, regarding this period:

Speaker-Hesse:

Then came that summer of 1914, and suddenly everything seemed totally transformed inside and out.

There is a brief experience of the first war years that I have never forgotten. I was visiting a huge lazarett, in search of some meaningful way, as a volonteer, to adapt to the changed world. In that field hospital for the wounded, I met an old maid, who had earlier enjoyed a good life as a financially independent unmarried woman, and now was serving as a nurse. She told me, in moving enthusiasm, how happy and proud she was to be able to experience this great period. I found it understandable, since for this lady the war was necessary to make an active, worthwhile life out of her lethargic and purely egoistical existence. But while she was communicating her happiness to me, in a corridor full of bandaged und bent-over, bullet-wounded soldiers, between rooms that were filled with amputees and dying men, it almost broke my heart. No matter how much I grasped the enthusiasm of this spinster, I could not approve of it. If for every ten wounded, there was one such enthusiastic nurse who came, then the price paid for this lady's happiness was somewhat expensive.

No, I could not share the joy over this great time, and so it came about that from the beginning, I suffered pitifully from this war, and for years, defended myself desperately against the catastrophe that had befallen us, while all around me, the world acted as if it were full of happy enthusiasm over this misfortune.

And when I then read newspaper articles of poets, who had discovered the blessing of war, and the calls of professors, and all the war poems issuing forth from the studies of the famous poets, then it became even more miserable for me.

The Young Maid Sits at Home and Sings

(Translation by Muriel Mirak-Weißbach and Gabriele Liebig)

Snow so white, snow so cool,

do you fall in distant lands

on my treasure’s dark brown hair,

on my love’s unmoving hand?

Snow so white, snow so cool,

will he not be cold?

say, does he lie in a show-white field

or in a deep dark wood?

Snow so white, snow so false,

leave my love in peace!

Why do you cover his curly hair

and make his eyes to close?

Snow so false, snow so white,

he is not dead at all;

perhaps he sits imprisoned

with water and with bread.

Perhaps he will be back quite soon,

may stand now by the door.

I have to wipe my tears away,

lest I can’t see his face.

At the End of Holiday in Time of War

(Translation by Muriel MiraK-Weißbach)

The old firm walking cane

I toss into damp grass,

a wretched end is near,

mine eyes are wet with tears.

I must force myself again,

I must say farewell again,

do, what I like not -

and all around me fresh blue air,

river, field, deep clefts and stream

and all earth's sound and sheen.

I must be content again,

I must long and yearn again,

and do alien deeds,

while within my heart

darkest pain doth smart

and golden dreams half-buried rest.

I spit softly in a bush:

you, whom I serve, all the time,

Minister, Excellency, General,

may the Devil fetch you!

Speaker:

Hesse was born on July 2, 1877 in Calw, a small town in the northern Black Forest. His parents were pietists (a conservative form of Protestantism), as their parents before them, and were closely tied to the missionary activity of the Basel Mission in India and Africa. (By the way, the ideas of the Basel Mission shaped the decision of Dr. Albert

Schweitzer – a contemporary of Hesse's - to set up a hospital for lepers in Africa.)

At the age of 20, Hesse left Calw and in 1904 moved into an old farmhouse in Gaienhofen on the Bodensee, to live as an independent writer, and he became famous.

Following a visit to India, in 1911, Hesse decided to live in Switzerland. In 1919, he bought a house in Montagnola (Tessin), where he began his most fruitful creative phase. He died in 1962.

The Dream

Having awoken from a nightmare's fright

I sit in bed and stare into the night.

I shudder deeply at my own soul's spark

that called upon such visions from the dark.

The sins I have committed in my dream,

are they my work? And are they, what they seem?

Alas, what this bad dream to me reveals

is bitter truth, is what my soul conceals.

I, by the uncorrupted judge's word,

have of the blotches on my nature heard.

Cool from the window night is breathing through

and shimmers, fog-like, in a greyish hue.

Oh sweet, bright day, please come and enter free

and try to heal what night has done to me.

Oh day, through me do all your sunlight send

so that, again, before you I may stand.

And make me, even if it is in pain,

of this bad hour's horror free again!

Speaker:

Hesse realized very early that he must become a poet. Again, we quote from his autobiography:

Speaker-Hesse:

From my thirteenth year on, one thing was clear to me: either I would become a poet or I would become nothing. Despite this clarity, I slowly gained another insight that was painful. One could become a teacher, pastor, doctor, worker, salesman, postman, even musician, painter or architect - for all professions in the world there was a way, there were pre-conditions, there was a school, there was education for beginners.

But for poets this did not exist! It was allowed, and was even considered an honor, to be a poet; that means, to be successful and famous as a poet, but then usually by that time one was unfortunately dead. To become a poet, though, that was impossible, to want to become one was ridiculous and a disgrace, as I was soon to realize.

Alone

Across the Earth are leading

many a road and bend,

yet all are speeding

to the selfsame end.

Be you riding or driving

as twosome or three,

the last of your steps

belongs but to thee.

For skill's not as valid,

nor all that is known,

as tackling the difficult

stuff on your own.

The Poet

Only on me, the lonely one,

the unending stars of the night shine,

the stone fountain whispers its magic song,

to me alone, to me the lonely one

the colorful shadows of the wandering clouds

move like dreams over the open countryside.

Neither house nor farmland,

neither forest nor hunting privilege is given to me,

what is mine belongs to no one,

the plunging brook behind the veil of the woods,

the frightening sea,

the bird whir of children at play,

the weeping and singing, lonely in the evening, of a man secretly in love.

The temples of the gods are mine also, and mine

the aristocratic groves of the past.

And no less, the luminous

vault of heaven in the future is my home:

Often in full flight of longing my soul storms upward,

to gaze on the future of blessed men,

love, overcoming the law, love from people to people.

I find them all again, nobly transformed:

Farmer, king, tradesman, busy sailors,

shepherd and gardener, all of them

gratefully celebrate the festival of the future world.

Only the poet is missing,

the lonely one who looks on,

the bearer of human longing, the pale image

of whom the future, the fulfillment of the world

has no further need. Many garlands

wilt on his grave,

but no one remembers him.

Speaker:

Let me quote another passage from the Presentation speech of the Nobel Prize for Literature, 1946:

"Hesse's maternal grandfather was the famous Indologist Gundert. Thus even in his childhood the writer felt drawn to Indian wisdom. When, as a mature man, he travelled to the country of his desire, he did not, indeed, solve the riddle of life; but the influence of Buddhism soon entered his thought, an influence by no means restricted to Siddhartha (1922) the beautiful story of a young Brahman's search for the meaning of life on earth. (...)

In Hesse's more recent work, the vast novel "Das Glasperlenspiel" (1943) [Magister Ludi] occupies a special position. It is a fantasy about a mysterious intellectual order, on the same heroic and ascetic level as that of the Jesuits, based on the exercise of meditation as a kind of therapy. The novel has an imperious structure in which the concept of the game and its role in civilization" is highlighted."

Speaker-Hesse:

When the war ended for me as well, in spring of 1919, I withdrew to a remote corner of Switzerland and became a hermit.

The belief in myself as a poet, and in the value of my literary work was deeply uprooted in me. Writing did not bring me any real joy any longer.

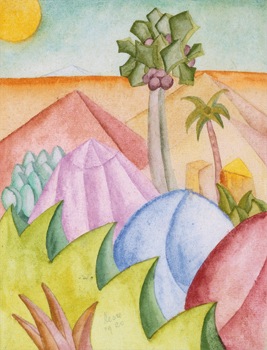

And yet, one day I discovered a totally new friend. At the age of 40, I suddenly began to paint. Not that I considered myself a painter, or that I wanted to become one. But painting is wonderful, it makes one happier and more patient. Afterwards, one does not have black fingers, as after writing, but red and blue.

Sonnenblumen 1927

Bei den Pyramiden 1920

bei Montagnola 1922

(Sonnenblumen 1927 - Bei den Pyramiden 1920 – bei Motagnola 1922)

In my poems, one often misses the usual respect for reality, and when I paint, then the trees have faces, and the houses laugh or dance, or cry, but whether the tree is a pear tree or a chestnut tree is most of the time not recognizable. I admit that even my own life very often seems to me to be a fairy tale.

Oh Burning World

Whether old or young, again and again I feel it:

A ridge in the night, on the balcony a woman stands,

a white stream in moonlight swings with gentle movement;

and longing rips my fearful heart out of my breast.

Oh burning world, oh fair woman on the balcony,

barking dog in the valley, distant rolling train,

oh how you lied, how bitterly you betrayed me then -

and yet you are still my sweetest dream and madness!

Oft sought I the way through dreadful "reality,"

where Professor, law, fashion, and markets reign,

but I always fled alone, disappointed and freed,

there, where dream and sweet jesting spring forth..

Humid night wind in trees, black gypsy girl,

world full of foolish longing and poetical scent,

glorious world, that always addicted me,

where your sheet lightning flashes, where your voice calls me!

Speaker:

... and further on in his autobiography, he writes:

Speaker-Hesse:

Briefly I want to say how my life describes a complete circle. In the years up to 1930 I still wrote some books, then to turn my back forever on this business.

The question, whether or not I actually should be counted among the poets was examined in two dissertations by hard-working young students, but it was not answered.

Steps

(Translation by Walter A. Aue)

Like ev'ry flower wilts, like youth is fading

and turns to age, so also one's achieving:

Each virtue and each wisdom needs parading

in one's own time, and must not last forever.

The heart must be, at each new call for leaving,

prepared to part and start without the tragic,

without the grief - with courage to endeavor

a novel bond, a disparate connection:

for each beginning bears a special magic

that nurtures living and bestows protection.

We'll walk from space to space in glad progression

and should not cling to one as homestead for us.

The cosmic spirit will not bind nor bore us;

it lifts and widens us in ev'ry session:

for hardly set in one of life's expanses

we make it home, and apathy commences.

But only he who travels and takes chances,

can break the habits' paralyzing stances.

It even may be that the last of hours

will make us once again a youthful lover:

The call of life to us forever flowers (...)

Anon, my heart! Do part and do recover!

- - - E N D - - -